What Beyoncé’s music says about the desire for freedom and recognition

In a book about Black women visual artists, UCLA professor Tiffany E. Barber draws comparisons to the legendary singer’s public reception

| May 14, 2025

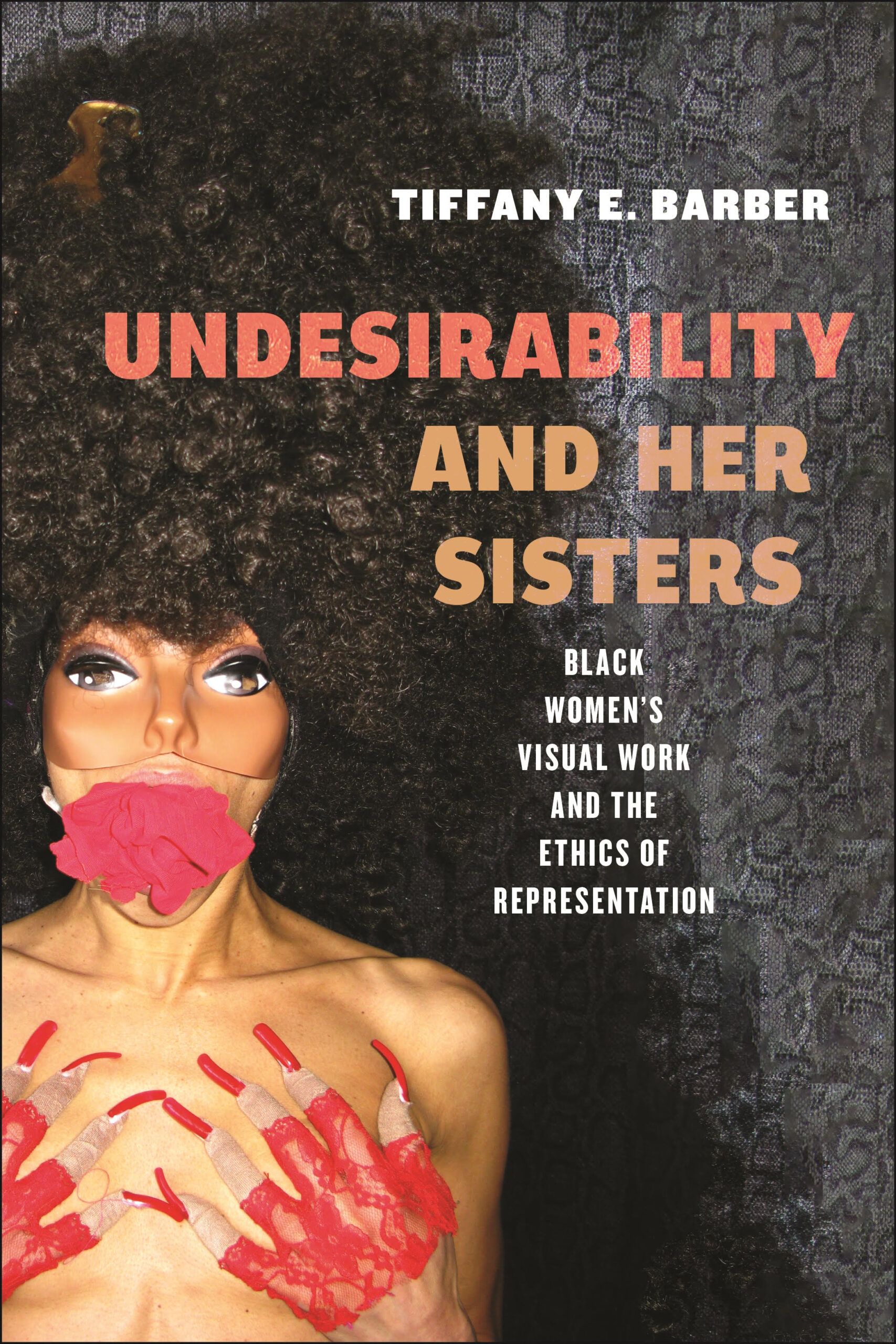

A new book by UCLA art history professor Tiffany E. Barber examines four prominent Black visual artists — Kara Walker, Wangechi Mutu, Xaviera Simmons and Narcissister — with a focus on what their work says about Black women’s bodies and their position at the intersection of race, gender, sexuality and class.

But in the introduction to “Undesirability and Her Sisters: Black Women’s Visual Work and the Ethics of Representation” (New York University Press), Barber turns her attention to the critical and popular reception of an even more famous Black woman artist: Beyoncé.

She writes that while Beyoncé’s music, videos and live shows seem to be “beyond critique,” her work is also “fraught with cross-racial desires for freedom and recognition as well as upward mobility for Black and non-Black fans alike.” In this adapted excerpt, she places Beyoncé’s landmark 2016 album “Lemonade” in cultural, historical and political context.

Seen as an expression of Black women’s pain and triumph over everything from infidelity to familial strife to present-day police brutality, “Lemonade” was heralded as a revolutionary work of Black feminism and restorative justice.

Beyoncé’s album is indeed visually sumptuous. In “Freedom,” the camera pans around a home as women sit outside or prepare a meal. The video cuts between black-and-white and rich jewel tones — visual cues that differentiate the past from the present. “That night in a dream,” Beyoncé recites in her introductory monologue, “the first girl emerges from a slit in my stomach. The scar heals into a smile.” “A girl crawls headfirst up my throat,” she goes on seconds later, “a flower blossoming out of the hole in my face” — a surrealist image conveyed through spoken text that merges motherhood with metamorphosis.

One of the scenes in the video for this song about breaking one’s chains features various cameos from other women — the mothers of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, actress Zendaya, and model Winnie Harlow, among them. This and every song on the album yield a single, but connected, narrative about strife and strength.

Viewers, listeners, and critics at the time labeled Beyoncé a cultural role model, a Black woman who had powerfully overcome the violence and weight of history by intertwining the personal and the political, a second-wave feminist adage. In “Freedom,” samples of two field recordings from 1948 and 1959 that document the work songs of Southern Black prisoners and Jim Crow–era African American speeches and spirituals, respectively, buttress this analysis.

“Lemonade” and the critical acclaim surrounding it propose an ethos of repair and redemption that I interrogate in this book — the very notion that Black women’s visual work must perform a recuperative function against historic and contemporary forms of violence. According to that logic, “Lemonade” and other similar examples in popular culture and fine art must elevate Black women’s practices of care and self-love in response to the most insidious forces of oppression: patriarchy, white supremacy, misogynoir, and state-sanctioned violence.

Case in point: Beyoncé’s experiences with her celebrity husband’s infidelity have melded the private devaluation of Black women by their partners with the national, sociopolitical devaluation of Black women in the United States. As a result, the album prompted wide-ranging conversations about womanhood, feminism, musical genres, and who can claim Black identity and culture in a purportedly post-gender, post-genre, post-Black world.

For thinkers and writers who celebrated “Lemonade”’s utopian vision of healing and community in troubled times, #BlackLivesMatter was the catalyst for the album’s intense engagement with Black culture and solidarity, especially among Black women. In so doing, the album also upheld a pervasive expectation concerning Black women’s art — that other forms of cultural production, high and low, must have the same political and social ends. This book invites readers to reconsider that expectation and to question the notion that only healing can lead to transformation.

This is not to deny the staying power of an album like “Lemonade.” Indeed, “Lemonade” has inspired countless think pieces, rave reviews, a new field of study named after the pop icon, and one crowd-sourced syllabus populated with more than two hundred Black feminist and womanist texts.

As writer, theologian, and lead organizer of the “Lemonade” syllabus Candice Marie Benbow puts it, Black women saw themselves as they watched chapter after chapter, lamenting the degradation they encountered in their intimate partner relationships and at the hands of a state “supposed to protect them.” “Lemonade” “left sisters exposed, yearning for a covering … for real healing and transformation.”

The album’s visual and sonic elements, in other words, were seen and felt as expressions of solidarity and sisterhood that coalesce into communal healing and wholeness. “Lemonade” also appeared to transcend taste barriers, solidifying the political, cultural, social, and aesthetic import — the value — of Black women’s creative labors on a national and global scale. In this merger lay a call for freedom, as the eponymous song suggests, for the most disrespected, unprotected, and neglected.

“Undesirability and Her Sisters” collates an altogether different and disagreeable vision, what I term the “undesirable.” The Black female bodies in recent works of public sculpture, collage, photography, and performance art by Kara Walker, Wangechi Mutu, Xaviera Simmons, and Narcissister are neither coherent nor curative.

Unlike conventional readings of “Lemonade,” and the greater ethos of self and communal empowerment, these artists eschew wholeness and cohesion and instead embrace such sensibilities as rupture and repulsion. Their visions of the negative and nonnormative upset and upend, resulting in unexpected pathways for Black women’s survival and self-understanding.

Source: What Beyoncé’s music says about the desire for freedom and recognition – UCLA Humanities